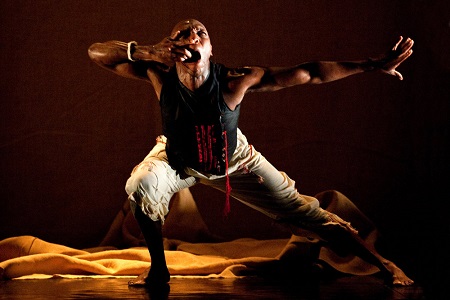

Dance virtuoso Vincent Mantsoe wows Toronto audiences at the Harbourfront Centre

The word “virtuoso” is one that has understandably lost its impact. Like all superlatives, it’s easy to toss around, and if it ever made readers perk up, it doesn’t anymore.

But when Danceworks curator Mimi Beck writes that Vincent Mantsoe — performing his two-part show NTU and Skwatta at Harbourfront Centre Theatre until January 31 — is a dancer of “breathtaking virtuosity,” she’s just stating the facts. He’s incredible.

Mantsoe grew up in South Africa, but he comes to Toronto via the whole world. Although his work is deeply rooted in traditional African dance, what grows from that soil is nourished by a wide range of international influences: Asian forms, martial arts, street dance, Western contemporary, and Aboriginal.

But labels are boring, and fusion too often serves the limited ambition of performing the feat of its own existence. The melting pot makes for thin gruel, unless the force that gathers those elements together accomplishes more than simply finding a suitable container for diversity. Mantsoe unequivocally transcends his eclectic curiosity — the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

The performance is comprised of two connected dances, which between them carry a balance of opposite tonalities. NTU unfolds in a purgatorial void, while Skwatta describes life in South Africa’s vibrant and chaotic squatter camps.

The term “Ntu” refers to a strain of African existentialism and signifies a generative source that’s deeper than emptiness and greater than nothingness. In Bantu philosophy, “being” and “force” are inseperable, and Mantsoe’s dancing expresses the intertwining of raw existence and ceaseless emergence.

There’s an unassuming little phrase in Mantsoe’s bio that slyly refers to this element: “He acknowledges the influence of spirituality in his creative work.” Well, that influence declares itself much more robustly in his actual dancing. There seems to be ancient energies at play, and the presence of spirits at once familiar and forgotten.

What does this actually look like? A good analogy may be found in the classical Persian music that accompanies NTU. Mantsoe dances to the wavering, wandering compositions of the Iranian Dastan Ensemble, and the exploratory gestures of the lute and sitar perfectly reflect his vast range of expression.

Mantsoe combines fierce architectural movements with the everyday phrasing of human bodies. His own immensely muscular body flutters and snaps disconcertingly, his feet trilling beneath him and then delivering wide, sweeping kicks and sudden stomps. His hands create the shapes that seem borrowed from rituals, and then they push and pull those stylized forms apart.

His emotional range is equally broad and intense. Late in NTU he breaks into a long bout of hysterical laughter; in Skwatta, he is periodically convulsed by sobs. All of it passes the way feelings do, like wind troubling the surface of the ocean, while beneath it the deep darkness rumbles on.

Another musical analogy: midway through Skwatta, Nina Simone’s voice fills the theatre, and the source of Mantsoe’s energy suddenly seems closer. There’s that ache and that wrath; there’s that old mix of defiance and supplication. There’s that heroic fragility we all feel.

The one failing of this show occurs in the uneven tension between the first and second part. Conceptually, NTU and Skwatta are well balanced, but proportionally they’re off-kilter. NTU reaches its limit, but Skwatta fails to find a satisfying conclusion. When it ended, I had no idea why.

Beyond that, the only other lack was in the seats. It was sad to find the the theatre so sparsely populated on opening night for such a rare performer. All the same, it occurred to me that Mantsoe is the type of artist who simply can’t be ignored. If he’s moving, something out there is watching.

Details

- NTU and Skwatta is playing at the Harbourfront Centre Theatre (235 Queens Quay West) until January 31.

- Shows run Thursday through Saturday at 8pm.

- Tickets range from $19 – $37 and may be purchased here.

Photo of Vincent Mantsoe by Val Adams.