by Jenna Rocca

The fact that Studies in Motion has a “Creators’ Note” rather than a “Director’s note” tells you a lot about the production. The Canadian Stage Company presents the Electric Company Theatre mashup of events and notions of Eadweard Muybridge’s life as a part of their current season.

For those of you aren’t familiar with the series of photos of galloping horses, Muybridge invented a method of photography that took a series of photos as a motion transpired. This zoopraxiscope is known as an early manifestation of what were to become motion picture cameras.

He, however, saw it as an opportunity to catalogue all possible forms of motion from the trivial (man walking) to the profound (woman with child).

Of course this necessitates a lot of nudity and I am pretty certain that this is the one production with the greatest amount of tasteful nudity you will ever see.

While this show is not a strict biopic, but rather, the product of collaboration between artists of many disciplines around Muybridge as a kind of theme, they do struggle to find plot-lines to imbue the otherwise independent occurrences in Muybridge’s life with some meaning.

Projections stating the year and “chapters” titles jump back and forth between his failed marriage, the summer he spent obsessively cataloguing motion, and his later life pondering the possibility of reuniting with the son he abandoned at an orphanage fifteen years earlier when his wife died. There is not much to like about him. He even goes so far as to murder a hundred year turtle (stolen from the veterinary school) through vivisection, all in the name of “science.”

Apparently the motion of the turtle’s heart beating will explain all other motions. No valid connections are made to validate this afterwards.

He does go on some rather disturbing (but more absurd) rants about how his project will perhaps explain all of existence. It was a Dr. Emmet Brown moment, I have to say.

If something did come from his photos, aside from mere cool-looking images, the notion of which he ironically chastises in the play, it is not explained in Studies in Motion.

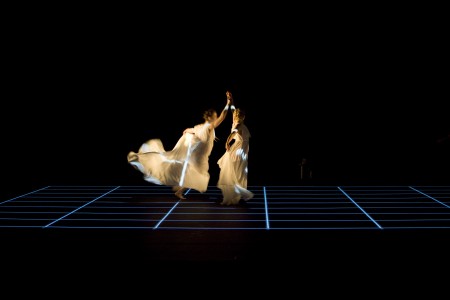

What I enjoyed the most about the show was the beautiful recreations of Muybridges photos in the form of balletic sequences. The actors would sporadically become one frame each in a sequence, or just prance across the stage in the thinnest flowing robes.

It was all beautifully assembled by choreographer Crystal Pite to Patrick Pennefather’s hypnotic and effective score.

Often when scenes would freeze and merge into one of these sequences, complete with stunning lighting by Robert Gardiner, I was not disoriented but relieved.

I am interested in one day seeing the opera based on Muybridge’s trial by Philip Glass, The Photographer. Oh, did I mention he is also the last person to get off of a homicide charge? That’s right, he ends up murdering his wife’s lover in cold blood and was found guilty but let off because in the olden days you were excused if you had “just cause.” Perhaps focusing solely on that chapter in his life would make for a stronger narrative thrust and ultimately more satisfying theatrical experience.

I felt that the piece would have been stronger without the character of Muybridge at all, but rather more like a ballet inspired by his work, because really these mostly nude dance and movement sequences were entirely astonishing.

My partner at the performance was perhaps less enthralled by these than I was, however agreed that they were the salvation of the production.

I recommend this piece exclusively because of these dances. I’ve really never seen anything like it.

Details

– playing at the Bluma Appel Theatre until December 18th

– tickets available at canadianstage.com are $22 – $80

Photo of Erin Wells, Anastasia Phillips by Tim Matheson.